|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

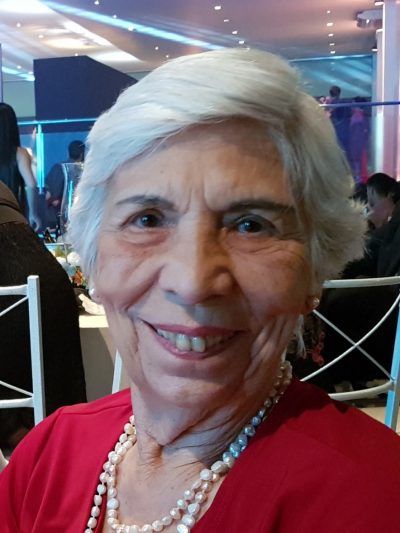

During the opening of the XVIII B-MRS Meeting in Balneário Camboriú (SC), on the night of September 22 of this year, Yvonne Primerano Mascarenhas, a retired professor of the University of São Paulo (USP), will give the Memorial Lecture Joaquim da Costa Ribeiro, an honor granted every year by B-MRS to a researcher with outstanding trajectory in Brazil. In the memorial lecture, Prof. Yvonne will talk about the evolution of crystallography (study of the structure of crystalline materials) in Brazil, a story she can personally narrate in the first person.

In fact, Professor Yvonne was the person who introduced and developed, since the early 1960s, the structural and molecular X-ray crystallography, now widely used in research, development and innovation in Brazil. The technique allows to fully know how the atoms and molecules that make up the organized structure of crystalline materials are arranged in space.

Yvonne Primerano was born on July 21, 1931 in Pederneiras, a small town in the State of São Paulo. When she was 10 years old, after living some years in the city of São Paulo, the family moved to the city of Rio de Janeiro because of the father’s work. Rio de Janeiro was the Capital of the country, and besides being safe at that time, it offered the family a warm reception and a wide range of possibilities, mainly in culture and education.

Yvonne’s secondary education was at Colégio Mello e Souza, a renowned private school in Rio. Due to her fondness for literature, in the last cycle of secondary school she opted for the so-called “classical course,” which reinforced the study of philosophy and literature and more superficially approached the natural sciences. However, it was in these chemistry classes taught by a great teacher – Albert Ebert – that Yvonne was captivated by the diversity of molecules created by nature and with the possibility of synthesizing them in the laboratory.

After graduating from secondary school, Yvonne chose to study chemistry, and after working hard for the university entrance exam, in order to fill the gaps of her humanistic education, in 1949 she entered the bachelor’s degree course in Chemistry at the University of Brazil, currently the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). There, once again, a special teacher intervened in her professional trajectory. It was Elisario Távora, professor of the Crystallography discipline. Professor Távora had just returned from the United States, where he had completed his doctorate from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) under the guidance of Professor Martin Julian Buerger – renowned crystallographer, author of innovations in techniques and instruments in the area. Thus, Yvonne, through Távora, had contact with the state of the art in crystallography techniques; mainly techniques based on X-ray diffraction, which led her to perceive the potential of the area. In young Yvonne’s mind, the idea was that studying the structure of molecules by X-ray diffraction might be a good idea.

Yvonne then felt she needed to learn more Physics, and in 1951 she started to study in this area her second degree at the current State University of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ). In 1954, she had two bachelor’s degrees and a solid baggage in Physical Chemistry. That year she married the physicist-chemist Sergio Mascarenhas, with whom she would form a family, and become a standard-bearer couple in the history of materials research in Brazil.

At the University of Brazil, Yvonne met Professor Joaquim da Costa Ribeiro and participated in the scientist’s research work. At that time, Costa Ribeiro – who a few years earlier had discovered the thermo-dielectric effect while studying Brazilian natural materials – was one of the very few researchers, along with Professor Bernhard Gross, who worked in Material Physics in Brazil. In fact, at that time research resources and efforts in the country were concentrated in nuclear and high energy physics.

In 1956, after living in Rio de Janeiro for fifteen years, Yvonne returned to live in the interior of the state of São Paulo. This time, she settled in São Carlos, a city of about 40 thousand inhabitants, with her husband and the couple’s first two children (a little boy and pregnant with a baby girl). The reason for moving to São Carlos was because the couple had been hired as full-time professors at a unit of USP that had been recently created in São Carlos, the School of Engineering of São Carlos (EESC).

If Rio de Janeiro had provided Yvonne the possibility of a solid preparation, São Carlos now offered both members of the Mascarenhas couple a series of benefits: belonging to an important university, teaching and research activities concentrated in one place (in Rio de Janeiro, Sergio worked in four different places) and, no less relevant, two wages enough to support the family. All of this in the practicability of a small city, saving several hours of driving to work every day. In addition, the couple would be free to develop research in the area that most interested them in that context: the application of Physics and Chemistry to the study and development of materials.

At EESC, a happy coincidence put Professor Yvonne, once again, on the path of structural crystallography. Forgotten in a corner, there was a medical X-ray machine that had been purchased by a French researcher who had spent some time at the institution. The device had not being used and was of no use to the engineering school. Professor Sérgio Mascarenhas then talked to the manufacturer and was able to exchange it for an X-ray diffraction instrument, which was used in the couple’s first experimental work in São Carlos. From these works, it became clear to Professor Yvonne that knowing the structure of materials was essential to know and modify their properties.

Between 1959 and 1960, the Mascarenhas spent 16 months in the city of Pittsburgh (United States) doing research internships with financial support from the Fulbright Commission, which was in Brazil since 1957. Yvonne intended to train in the study of the structure of materials by X-ray diffraction with a group in the Carnegie Institute of Technology. But when she met the group, she was disappointed. It was then that, by chance, she met the Brazilian physicists Ernesto and Amélia Hamburguer, who were at the University of Pittsburgh doing a doctorate and a master’s degree, respectively. The Hamburguers suggested that Professor Yvonne Mascarenhas should try to do an internship in the Crystallography laboratory coordinated by Professor George Jeffrey at the University of Pittsburgh.

After a few weeks attending a Crystallography course taught by Professor Jeffrey, Professor Yvonne Mascarenhas began working in his research group, where, among other projects, she performed the experimental work of her doctoral thesis, which consisted in obtaining the position of the atoms of a material with magnetic properties by means of X-ray diffraction. At that time, applying this technique was a very complex and time-consuming task due to the limitations of the available equipment, including computers. At the end of her internship at the University of Pittsburgh, she had acquired skills and knowledge that qualified her to work with X-ray crystallography.

After returning to Brazil in 1961, Yvonne (who at that time was the only one working with structural crystallography in Brazil) initiated the Crystallography Laboratory of São Carlos (which would become the first structural crystallography laboratory in the country). The implementation of the laboratory infrastructure and the recruitment and training of its multidisciplinary and international team intensified in the 1970s and continued into later years.

In 1963, after processing the experimental results obtained in Pittsburgh, challenging due to the lack of computers at EESC, Yvonne defended her doctoral thesis titled “Determination of crystalline structures by X-ray diffraction: study of Manganous Formate Dihydrate.”

In 1971, Dr. Yvonne P. Mascarenhas obtained the title of Associated Professor at EESC. In 1981, she became a full professor at the Institute of Physics and Chemistry of São Carlos (IFQSC), another USP unit founded in 1971 in the Sao Carlos Campus. When, in 1994, this unit was split into the Institutes of Physics (IFSC) and Chemistry (IQSC), Professor Yvonne P. Mascarenhas remained in IFSC until her compulsory retirement in 2001, when she became collaborating researcher at the institution. Over the ensuing years, Yvonne began to lead projects related to science teaching and diffusion in public elementary and middle level schools.

Throughout her career, Professor Yvonne P. Mascarenhas has accomplished scientific internships as visiting researcher at some of the world’s most renowned institutions: Princeton University and Harvard University (United States), the National Polytechnic Institute of Mexico, and the University of London (United Kingdom).

She has also had several leadership roles, which until today are predominantly performed by men in the Brazilian academic environment. Within USP São Carlos, she has been the department head, the first director of the Institute of Physics of São Carlos (IFSC) and vice-coordinator of the Institute of Advanced Studies – Polo São Carlos, among other positions. In addition, she led the creation of the Brazilian Society of Crystallography (current Brazilian Crystallographic Association), founded in 1971, and was the president of the society.

Here are some of the many tributes and honors she has received: Distinguished Women in Chemistry or Chemical Engineering Awards of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (2017), the title of emeritus professor of the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development, CNPq (2013), the admission to the Brazilian National Order of Scientific Merit in the Grand Cross Class by the Presidency of Brazil (1998) and the Simão Mathias Medal of the Brazilian Chemical Society (1998). In addition, the researcher has been a full member of the Brazilian Academy of Sciences since 2001.

Over the six decades of working in structural crystallography, Yvonne Primerano Mascarenhas has participated in dozens of projects in various areas that need structural information on materials or molecules, interacting closely with materials scientists, engineers, chemists, physicists, biologists, biochemists, physicians and others. During the period, she supervised 40 master’s and doctoral studies, and coauthored more than 180 articles in international scientific journals. The laboratory created by Yvonne (now called Multiuser Laboratory of Structural Crystallography) has directly generated more than 1,000 articles published in scientific journals and has enabled researchers in many Brazilian states and Latin American countries to perform X-ray diffraction.

Sixty years after the first Brazilian works with structural X-ray crystallography, around 200 structural crystallographers work in Brazilian universities, among them, the pioneer Yvonne Primerano Mascarenhas, now at the age of 87, who still actively participates in scientific research.

Here is a brief interview with this leading scientist.

B-MRS Newsletter: Through crystallography, you have revealed information that is essential to many research projects in many areas. Could you tell us which are the most impacting works in the materials area in which you have participated.

Yvonne Primerano Mascarenhas:

In this work, carried out during an internship at the Department of Crystallography of Birkbeck College, University of London, we were able to contribute to the elucidation of oxytocin, an important hormone produced by the pituitary gland, which in the case of women plays an important role in the stages of childbirth and lactation.

The measurements performed on the diffractograms of the various types of polyurethane allowed the quantitative determination of the crystallinity percentages of the different samples and related them with other spectroscopic results.

The structural determination of the material under study by low temperature X-ray diffraction allowed us to characterize a low temperature crystallographic transition that is important to understand the magnetic properties of the studied material.

The determination of the molecular structure of this enzyme, which is one of the components of rattlesnake venom, allowed to better understand its biological action.

This publication was the result from work done at the University of Pittsburgh during my first internship abroad. The substance under study is a barbiturate that crystallizes with a water molecule. The structural determination revealed the presence of a bifurcated hydrogen bond that had already been predicted theoretically but was experimentally observed for the first time in this crystal.

This is one of a series of works carried out in collaboration with the Petrobras research center (CEMPES) to analyze changes produced in a series of zeolites that are used as catalytic cracking of petroleum. The results obtained allowed to better understand the mechanisms of catalysis and to suggest other modifications aiming at higher yields.

B-MRS Newsletter: At the XVIII B-MRS Meeting you will give the Memorial Lecture “Joaquim da Costa Ribeiro.” At the end of the event, B-MRS will award students the “Bernhard Gross” Award. You have personally met these two pioneers of materials research in Brazil (Costa Ribeiro and Gross). Could you briefly tell us about your relationship with them?

Yvonne Primerano Mascarenhas: To talk about these individuals in a small paragraph is quite insufficient. Costa Ribeiro and Gross were our mentors in our first research and scientific education activities. We interacted with both scientists during our undergraduate years at the then University of Brazil, currently UFRJ. We had a strong research contact with Bernhard Gross, who visited São Carlos periodically until his death, guiding our activities both experimental and theoretical and guiding some young physicists who had joined our laboratory. Costa Ribeiro supported us quite a bit since our arrival in São Carlos, both with letters of recommendation to the director of EESC, as well as yielding a Wulf electrometer that allowed us to immediately start the dielectrics research. He later spent several years outside Brazil as the representative of Brazil at the Atomic Energy Commission in Vienna and died prematurely a few years after his return to Brazil.

B-MRS Newsletter: You have four children who were raised while you were developing an important scientific career, including holding leadership positions. You usually declare that you did not believe your professional life was undermined because you were a woman. Could you tell us how you managed to reconcile family and professional life at a time when there was no maternity leave in Brazil, and women used to be fired when becaming mothers?

Yvonne Primerano Mascarenhas: Living in a small town enables one to have a great family relationship with children, relatives and friends. So I believe that the decision to move from Rio de Janeiro to São Carlos played a very important role in my professional performance. In addition, I have always valued the help I received from the excellent people who supported me in my domestic needs and in the care of my children. I was very lucky to have this invaluable help from several people who were in my life sharing responsibilities in an interpersonal exchange of much love and respect.

B-MRS Newsletter: Please leave a message for our younger readers who are starting a career as scientists or are contemplating this possibility.

It is never too much to remind them that the economic and social situation of our country will only improve when we can improve the cultural and scientific level of our people, as well as establish notions of responsible, ethical and moral conduct that lead to the good use of our potential natural resources (agriculture, mineral reserves and industrial and commercial processes) and the proper use of taxes collected from the population. In order to do so, the commitment of our young people is crucial both in the educational area and in the exercise of citizenship. I am well aware that it is a great demand, but I am sure that with well-focused effort on these goals, they will be able to achieve great results.

[Paper: Antimicrobial Activity and Cytotoxicity to Tumor Cells of Nitric Oxide Donor and Silver Nanoparticles Containing PVA/PEG Films for Topical Applications. Wallace R. Rolim, Joana C. Pieretti, Débora L. S. Renó, Bruna A. Lima, Mônica H. M. Nascimento, Felipe N. Ambrosio, Christiane B. Lombello, Marcelo Brocchi, Ana Carolina S. de Souza, and Amedea B. Seabra. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 2019, 11 (6), pp 6589–6604. DOI: 10.1021/acsami.8b19021. ]

Synergistic anticancer films

A team of researchers from Brazilian universities developed a new film material that contains and releases, simultaneously, silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) and nitric oxide (NO) – two active substances known for their antimicrobial and anticancer activity. Tested by the scientific team, the material proved to be effective in eliminating various types of bacteria and cells from certain types of cancer. The characteristics of the film make it promising to topically treat malignant tumors or infectious lesions.

The study, recently published in ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces (Impact Factor 8.097), was developed during the Master’s research work of Wallace Rosado Rolim, guided by Professor Amedea Barozzi Seabra, and defended this year in the postgraduate program in Science and Chemical Technology of the Federal University of ABC (UFABC). The work also involved, through scientific collaborations, knowledge and experimental techniques of Biology and Biomedicine areas. “I emphasize the importance of interdisciplinarity and teamwork for the success of scientific and technological research,” says Professor Seabra, who is the corresponding author of the article.

The idea of developing this biomaterial (a material planned to interact with a biological system for medical diagnostic or treatment) came up in discussions between Rolim and his advisor. “We were looking for new strategies for controlled, localized and sustained release of actives such as nitric oxide molecules associated with silver nanoparticles, for biomedical applications,” reports Professor Seabra. The scientific duo had the idea of bringing together the two therapeutic assets in a single material that was able to topically release them. “We were looking for a synergistic action of these two assets,” says Seabra.

Thus, Professor Seabra and Rolim, with the collaboration of the Master’s student Joana Claudio Pieretti, endeavored to develop the material. The team was able to prepare films made from a composite material, whose matrix consists of a polymer, known as PVA, added with another polymer, called PEG, which made the matrix more flexible. Both polymers are non-toxic and biocompatible. During the preparation of the films, they added silver nanoparticles and a nitric oxide donor substance (the GSNO molecule, which, spontaneously, decompose and generate nitric oxide).

The same group prepared the silver nanoparticles using a simple, inexpensive method that is friendly with the environment and living organisms, also developed by Rolim in his Master’s work. In the method, which was reported in an article published earlier this year (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.08.203), green tea extract is used to generate the nanoparticles from silver nitrate, as shown in this figure:

In order to compare the antimicrobial and anticancer effects, the team prepared several types of films: some formed by the pure matrix (PVA/PEG), others containing silver nanoparticles or nitric oxide donors in different concentrations, and the last containing both therapeutic agents in the same matrix. After analyzing all the films using various characterization techniques to accurately determine their composition and morphology, Professor Seabra and her students studied how the release of nitric oxide and silver nanoparticles occurred.

Finally, the films were sent to the collaborators from other research groups to perform the biological assays, which were performed in vitro (i.e., outside living organisms and within environments with controlled conditions). At UFABC, the groups of professors Ana Carolina Santos de Souza Galvão and Christiane Bertachini Lombello focused on the anticancer action of the biomaterial, using cervical and prostate cancer cells. On the other hand, the tests related to the antibacterial activity of the films were carried out at the São Paulo State University of Campinas (UNICAMP), by Professor Marcelo Brocchi’s group, which involved tests with several types of bacteria, including the well-known Escherichia coli and Staphylococus aureus.

The tests showed that the films containing both therapeutic assets presented the best results in the elimination of bacteria and mainly of cancerous cells, as this figure illustrates:

As a result, the synergism between silver and nitric oxide nanoparticles, which Seabra and Rolim had looked for since the beginning of the Master’s research work, was proven. In one of the assays, to cite one example, less than 25% of the cancer cells remained alive (viable) after being treated with these films for 24 hours.

The material developed by the UFABC team brings the possibility of implementing a new therapeutic strategy for some cancerous tumors and infectious lesions, based on the simultaneous release of nitric oxide and silver nanoparticles, directly at the affected site, from a film. Seabra explains that “In practice, this film can be applied, for example, in a tissue (such as the skin or mucosa) or an organ, for antimicrobial or antitumor actions.” By releasing therapeutic amounts of the agents directly at the site of interest, it avoids unwanted release in healthy organs and/or tissues and thus prevents possible side effects, Seabra adds.

This work received financial support from the Brazilian agencies CNPq, FAPESP and CAPES. The first author of the paper, Wallace Rosado Rolim, developed his master’s research work with a grant from UFABC.

B-MRS is pleased to present the committee responsible for organizing the process that at the end of this year will conclude with the election of the next Executive Board and members of the Council of the society. All active members with paid 2019 annuity will be eligible and may vote.

The members of the Electoral Commission are:

The commission will soon be making available the election calendar and other information on the B-MRS website. The information will be disclosed in B-MRS’s e-newsletter and social media, as well as sent by e-mail to the active members.

The current Executive Board of B-MRS thanks the participation of Professors Cena, Cremona and Péres in the organization of this important process of the Society.

Professor Aldo Jose Gorgatti Zarbin (UFPR, Department of Chemistry), a member of B-MRS , is one of the 58 scientists in the world and the only one in Latin America who participated in a special paper on the future of Chemistry, published in Nature Chemistry in 22 March, on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of the journal. Zarbin and the other scientists were invited by this renowned scientific journal to write about the most challenging and interesting aspects regarding the development of their research lines.

Professor Zarbin works mainly in the synthesis of nanomaterials in liquid/liquid interfaces, their characterization and their applications in the generation and storage of energy, catalysis and sensors.

The special article in Nature Chemistry, which includes the vision of the Brazilian scientist, can be accessed here: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41557-019-0236-7.

Reference of the paper: Charting a course for chemistry. Alán Aspuru-Guzik, Mu-Hyun Baik, […]Hua Zhang . Nature Chemistry, volume 11, pages 286–294 (2019). https://doi.org/10.

As of March, with the incorporation of a University Chapter (UC) unit at the Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul (UFMS), Brazil’s five regions are present in the map of the B-MRS’s UCs. In addition, the map of the program gains a new spot in the state of São Paulo, through the participation of a team in the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP), campus of São José dos Campos.

The UCs program, which now has 11 units, brings together undergraduate and graduate student teams from Brazilian universities around complementary activities for academic education.

According to the president of UFMS UC, Gustavo Sander Larios, M.S., the creation of the UC was motivated by the desire to increase interaction among students from different laboratories, departments and research groups. Thus, the team, which is made up of undergraduate, masters and PhD students from the areas of Materials Science, Physics and Chemistry, will stimulate the organization of seminars and scientific meetings involving members of the UC and researchers from B-MRS. “We intend to promote activities that stimulate the development of scientific knowledge, given the national and international research trends, provided through the interaction among the UC members,”adds Larios. The supervisor of this unit is Professor Cícero Rafael Cena da Silva.

At the UC of the University of São José dos Campos, UNIFESP, the main objective is to disseminate Materials Engineering and Science among university students from all over the Vale do Paraíba region and also in society as a whole, says the master’s Verônica Ribeiro dos Santos, president of the unit, and Professor Manuel Henrique Lente, the supervisor of the UC. The team intends to “divulge the concept of Materials Engineering, since for many it is still unknown, given the great diversity of areas of expertise that the professional in this field is capable of carrying out.” According to Verônica Ribeiro dos Santos and professor Manuel Henrique Lente, the group aspires, in the future, to make their UC an extracurricular source of scientific and technological knowledge and to increase the number of members. Some of the activities the team intends to promote are: seminar cycles involving students and researchers from UNIFESP and other institutions; lectures by representatives of S&T support agencies, class entities, industrial sectors, etc.; technical visits to R&D institutes, companies and incubators; summer courses; dissemination lectures in high schools. In order to carry out the activities, the UC has a comprehensive team of 24 undergraduate students (Bachelor’s degree in Science and Technology, and Materials Engineering), three master’s and one doctoral students (Post-graduation in Materials Science and Engineering, PPGECM), all from UNIFESP.

Get to know B-MRS’s UCs Program and the eleven units it has so far in the states of Mato Grosso do Sul, Minas Gerais, Pará, Pernambuco, Piauí, Rio Grande do Sul and São Paulo: https://www.sbpmat.org.br/en/university-chapters/ucs-da-sbpmat/

On behalf of the Organizing Committee, we invite you to participate the XVIII Brazil MRS Conference (XVIII B-MRS Meeting), which will be held in the city of Balneário Camboriú-SC, in the period of September 22nd-26th, 2019.

Don’t miss the opportunity of participating this important international scientific event on Materials Science and submit your Abstract for Oral or Poster Presentation.

Deadline for Abstract submission: April 15th, 2019.

Web site: https://www.sbpmat.org.br/

With kind regards,

Ivan H. Bechtold – Chair

Hugo Gallardo – Co-chair

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|