The “old-fashioned” sewing thread universally used, for example, to sew buttons, has recently been transformed by a Brazilian scientific team into an electrically conductive and multifunctional material. In fact, the various uses of this new sewing thread go far beyond sewing. It works very well as a mini electric heater, as a component of supercapacitors (devices that store and release energy, similar to batteries) and as a bactericidal agent. In addition, the thread is flexible and comfortable to the touch, and retains its electronic properties even after being washed, twisted, curled or folded repeatedly.

With these characteristics, this fiber can play an important role in wearable electronics – the set of electronic devices designed to be worn on the human body, incorporated into clothing or accessories.

“As the thread is a basic element for the design of textiles, we imagine that any wearable product can make use of this technology”, says Helinando Pequeno de Oliveira, a professor at the Brazilian Federal University of the Vale de São Francisco (Univasf) and leader of the scientific team that developed the conductive and bactericidal thread. Together with three other authors, all linked to Univasf, Oliveira authors an article reporting this work, which was recently published in the journal ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces.

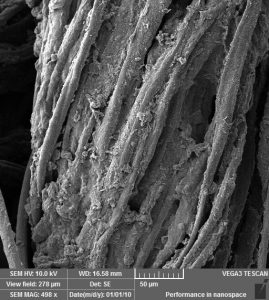

The conductive and bactericidal fiber of Oliveira and his collaborators is made of a composite material: cotton thread of 0.5 mm diameter, coated with carbon nanotubes and polypyrrole. The resulting material presents, in addition to high electrical conductivity, good electrochemical activity – necessary characteristic for it to be used in supercapacitors.

To make the conductive fiber, the Univasf team developed a very simple process, formed by two main stages. In the first step, pieces of cotton thread are submerged in a paint of carbon nanotubes, previously modified in order to increase their interaction with the cotton. As a result, the thread is coated by a continuous network of interconnected nanotubes.

The second step is intended to coat the fibers with a second material: polypyrrole. To do this, a solution is initially formed by pyrrole and the solvent hexane, in which the fibers coated with nanotubes are submerged. Thereafter, another solution is poured over this preparation. The second solution consists of water and some compounds, which will be incorporated in very small amounts into the chemical composition of the polypyrrole in a process called “doping” of the material. At the interface between both solutions, which do not mix, the small pyrrole molecules are bound together, resulting in the formation of polypyrrole macromolecules that are deposited on the surface of the fibers. This process, in which a polymer forms at the interface between two solutions, is called “interfacial polymerization”. “Given the good polypyrrole doping level (optimized for this synthesis) and its strong interaction with the functionalized nanotubes, the resulting fibers display excellent electrical properties,” says Professor Oliveira.

The scientific team also produced some variants of this sewing conductive thread. For example, a fiber without carbon nanotubes and another fiber whose polypyrrole coating was produced by means of non-interfacial polymerization. However, the lines with carbon nanotubes and interfacial polymerization showed the best electrical and electrochemical performance.

Heaters and supercapacitors made of cotton fibers

“The high electrical conductivity (together with the good porosity of the material) made of the material a great prototype for application in electrodes of supercapacitors”, says Oliveira. “These properties also made it possible to use it as an electric heater with very low operating voltages (of the order of a few volts). In addition to these applications, the antibacterial potential of the matrix”, he adds.

In addition to testing the performance of the conductive and bactericidal fiber in isolation in the laboratory, Oliveira and his collaborators developed a proof of concept. “We used a needle to sew the thread in a glove”, says the professor. With this we could monitor the temperature that the hand, wearing this glove, would reach when we connected the device to a power supply,” he explains.

The heating system tested on the glove can be adapted to a variety of contexts, such as an ambulatory version of thermotherapy (therapeutic heating of body regions, which is often used in physiotherapy sessions)with the added advantage of antibacterial action. This property is particularly interesting in materials that are used in contact with the skin, since, in this way, they avoid diseases and odors. In the case of polypyrrole, the action occurs when the material electrostatically attracts the bacteria and promotes the breakdown of its cell wall, inhibiting its proliferation.

A possible wearable product based on the conductive sewing thread is a thermal jacket.It could be powered by a solar cell incorporated into the jacket, or by means of triboelectric devices, which would reap the energy generated by the user’s movement of the jacket.The resulting energy would be stored in a supercapacitor made with the conductive fiber. Tailored to the jacket, the supercapacitor would provide electricity to the heater when needed.

Another example is the energy storage t-shirt, in which Professor Oliveira’s group is currently working to generate a marketable product. We are currently optimizing the production of supercapacitors in pieces of cotton and lycra fabrics as a way to connect them directly to portable power generators, thus enabling the development of energy storage t-shirts,” says Oliveira.

Science and technology developed in the backlands

The work reported in the ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces and their developments were fully carried out at the Materials Science Research Institute of Univasf, on the campus of the municipality of Juazeiro, located in the north of the state of Bahia. Univasf, which has six campuses located in the interior of the states of Bahia, Pernambuco and Piauí, was created in 2002 and inaugurated in 2004. In the same year, Oliveira became a professor at the institution.

The development of the conductive cotton lines was born from a thread of research on electronics and flexible devices, created in 2016. In 2017, the idea became the theme of the master’s work of Ravi Moreno Araujo Pinheiro Lima, guided by Professor Helinando Oliveira, within the Postgraduate Program in Materials Science at Univasf – Juazeiro, created in 2007. Post-doc José Jarib Alcaraz Espinoza, who was optimizing syntheses of conductive polymers for supercapacitors, adapted a methodology to interfacial polymerization in cotton. With this, the researchers realized that the conductor lines worked as good supercapacitor electrodes, and fabricated these devices. At the same time, with the collaboration of Fernando da Silva Junior, a doctoral student of the institutional postgraduate program Northeast Network of Biotechnology, the team tested the action of the material against the bacterium Staphylococcus aureus, responsible for a series of infections of varying degrees of severity not human.

“These results reflect Brazil’s investment in the internalization of its network of federal teaching and research institutions. With this, the migration of the sertanejo towards the great capitals in the search for knowledge has been reduced. Now there is also more science being produced in the northeastern backlands”, says Professor Oliveira. “However, recent cuts in S & T have launched a huge cloud of uncertainty about the future of science in the country (and in particular about these young institutions). The Brazilian government does not have the right to throw so many dreams in the trash. Science needs to overcome this crisis,” completes the researcher.

[Paper: Multifunctional Wearable Electronic Textiles Using Cotton Fibers with Polypyrrole and Carbon Nanotubes. Ravi M. A. P. Lima, Jose Jarib Alcaraz-Espinoza , Fernando A. G. da Silva, Jr., and Helinando P. de Oliveira. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 2018, 10 (16), pp 13783–13795. DOI: 10.1021/acsami.8b04695]