O artigo científico de autoria de membros da comunidade brasileira de pesquisa em Materiais em destaque neste mês é: Multifunctional Wearable Electronic Textiles Using Cotton Fibers with Polypyrrole and Carbon Nanotubes. Ravi M. A. P. Lima, Jose Jarib Alcaraz-Espinoza , Fernando A. G. da Silva, Jr., and Helinando P. de Oliveira. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 2018, 10 (16), pp 13783–13795. DOI: 10.1021/acsami.8b04695

Linha de algodão condutora para costurar eletrônicos vestíveis

A “velha conhecida” linha de costura, universalmente usada, por exemplo, para pregar botões, foi recentemente transformada por uma equipe científica brasileira em um material condutor de eletricidade e multifuncional. De fato, os usos desta nova linha de costurar vão muito além da costura. Ela funciona muito bem como mini aquecedor elétrico, como componente de supercapacitores (dispositivos que armazenam e liberam energia, similares às baterias) e como agente bactericida. Além disso, a linha é flexível e confortável ao toque, e conserva suas propriedades eletrônicas mesmo depois de lavada, torcida, enrolada ou dobrada repetidas vezes.

Com essas características, a fibra pode cumprir um papel importante na eletrônica vestível – o conjunto de dispositivos eletrônicos planejados para serem usados sobre o corpo humano, incorporados a roupas ou acessórios.

“Como a linha é um elemento básico para a concepção de têxteis, imaginamos que qualquer produto vestível possa fazer uso desta tecnologia”, diz Helinando Pequeno de Oliveira, professor da Universidade Federal do Vale de São Francisco (Univasf) e líder da equipe científica que desenvolveu a linha condutora e bactericida. Junto a outros três autores, todos ligados à Univasf, Oliveira assina um artigo sobre o assunto, que foi recentemente publicado no periódico científico ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces (fator de impacto= 7,504).

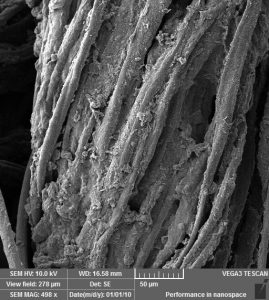

A fibra condutora e bactericida de Oliveira e seus colaboradores é feita de um material compósito, formado por linhas de algodão de 0,5 mm de diâmetro, revestidas com nanotubos de carbono e polipirrol. O material resultante apresenta, além de alta condutividade elétrica, boa atividade eletroquímica – característica necessária para que possa ser usado em supercapacitores.

Para fabricar a fibra condutora, a equipe da Univasf desenvolveu um processo bastante simples, formado por duas etapas principais. Na primeira etapa, pedaços de linha de algodão são submergidos em uma tinta de nanotubos de carbono quimicamente modificados de modo a aumentar sua interação com o algodão. Como resultado, a linha fica revestida por uma rede contínua de nanotubos interconectados.

A segunda etapa é destinada a revestir as fibras com um segundo material: o polipirrol. Para isso, inicialmente, prepara-se uma solução formada pelo composto pirrol e o solvente hexano, na qual se submergem as fibras revestidas com nanotubos. Em seguida, verte-se, em cima desta preparação, uma outra solução, formada por água e alguns compostos que acabarão se incorporando em quantidades muito pequenas à composição química do polipirrol num processo chamado “dopagem” do material. Na interface entre ambas as soluções, as quais não se misturam, ocorre então a união das pequenas moléculas de pirrol, resultando na formação de macromoléculas de polipirrol que se depositam na superfície das fibras. Este processo, no qual um polímero se forma na interface entre duas soluções, é chamado de “polimerização interfacial”. “Dado o bom nível de dopagem do polipirrol (otimizado para esta síntese) e a sua forte interação com os nanotubos funcionalizados, as fibras resultantes apresentam ótimas propriedades elétricas”, diz o professor Oliveira.

A equipe científica também produziu algumas variantes dessa linha de costurar condutora. Por exemplo, uma fibra sem nanotubos de carbono e outra fibra cujo revestimento de polipirrol foi produzido por meio de uma polimerização não interfacial. Entretanto, as linhas com nanotubos de carbono e polimerização interfacial mostraram o melhor desempenho elétrico e eletroquímico.

Aquecedores e supercapacitores em fibras de algodão

“A alta condutividade elétrica (em conjunto com a boa porosidade do material) fez do material um ótimo protótipo para aplicação em eletrodos de supercapacitores”, diz Oliveira. “Estas propriedades também viabilizaram o seu uso como aquecedor elétrico com tensões de operação bem baixas (da ordem de poucos volts). Junto a estas aplicações, se soma o potencial antibacteriano da matriz”, completa.

Além de testarem o desempenho da fibra condutora e bactericida de forma isolada no laboratório, Oliveira e seus colaboradores desenvolveram uma prova de conceito. “Usamos uma agulha para costurar a linha em uma luva”, conta o professor. “Com isso poderíamos monitorar a temperatura que a mão, vestindo esta luva, atingiria quando conectássemos o dispositivo a uma fonte de alimentação”, explica.

O sistema de aquecimento testado na luva pode ser adaptado a diversos contextos, como por exemplo uma versão ambulatória da termoterapia (aquecimento terapêutico de regiões do corpo, que é frequentemente utilizado em sessões de fisioterapia), com a vantagem adicional da ação antibacteriana. Essa propriedade é particularmente interessante em materiais que são usados em contato com a pele, já que, dessa maneira, evitam doenças e odores. No caso do polipirrol, a ação ocorre quando o material atrai eletrostaticamente as bactérias e promove o rompimento de sua parede celular, inibindo a sua proliferação.

Um possível produto vestível baseado na linha de costurar condutora é um casaco térmico. Ele poderia ser alimentado por meio de uma célula solar incorporada ao casaco, ou por meio de dispositivos triboelétricos, que colheriam a energia gerada pelo movimento do usuário do casaco. A energia resultante seria armazenada em um supercapacitor feito com a fibra condutora. Costurado ao casaco, o supercapacitor forneceria eletricidade ao aquecedor quando necessário.

Mais um exemplo é o da camiseta armazenadora de energia, na qual o grupo do professor Oliveira está trabalhando atualmente com o objetivo de gerar um produto comercializável. “No momento estamos otimizando a confecção de supercapacitores em peças de tecidos à base de algodão e lycra, como forma a conectá-los diretamente a geradores de energia portáteis, viabilizando assim o desenvolvimento de camisetas armazenadoras de energia”, revela Oliveira.

Ciência e tecnologia desenvolvida no sertão nordestino

O trabalho reportado no artigo da ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces e seus desdobramentos foram totalmente realizados no Instituto de Pesquisa em Ciência dos Materiais da Univasf, no campus do município de Juazeiro, localizado ao norte do estado da Bahia. A Univasf, que possui seis campi distribuídos no interior dos estados da Bahia, Pernambuco e Piauí, foi criada em 2002 e inaugurada em 2004. No mesmo ano, Oliveira tornou-se professor da instituição.

O desenvolvimento das linhas de algodão condutoras nasceu de uma linha de pesquisa sobre eletrônicos e dispositivos flexíveis, criada em 2016. Em 2017, a ideia virou tema do trabalho de mestrado de Ravi Moreno Araujo Pinheiro Lima, com orientação do professor Helinando Oliveira, dentro do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciência dos Materiais na Univasf – Juazeiro, criado em 2007. O pós-doc José Jarib Alcaraz Espinoza, que estava otimizando sínteses de polímeros condutores para supercapacitores, adaptou uma metodologia à polimerização interfacial em algodão. Com isso, os pesquisadores perceberam que as linhas condutoras funcionavam como bons eletrodos de supercapacitores, e fabricaram esses dispositivos. Ao mesmo tempo, com a colaboração de Fernando da Silva Junior, doutorando do programa de pós-graduação institucional Rede Nordeste de Biotecnologia, a equipe testou a ação do material contra a bactéria Staphylococcus aureus, responsável por uma série de infecções de diversos graus de gravidade no ser humano.

“Estes resultados refletem o investimento do Brasil na interiorização de sua rede de instituições federais de ensino e pesquisa. Com isso, a migração do sertanejo rumo às grandes capitais na busca por conhecimento vem sendo reduzida. Agora há também mais ciência sendo produzida no sertão nordestino”, afirma o professor Oliveira. “No entanto, os recentes cortes em C&T têm lançado uma enorme nuvem de incerteza sobre o futuro da ciência no país (e em particular sobre estas jovens instituições). O governo brasileiro não tem o direito de jogar tantos sonhos no lixo. A ciência precisa superar mais esta crise”, completa o pesquisador.