|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Guess what it is.

It is perhaps the best known among biomimetic products (products developed by humans to imitate living beings that have been “developed” by nature over many millions of years).

It is an invention that became innovation (entered the market) and after some time it was widely accepted by consumers. Its use spread on planet Earth (on land, water and air) and reached the Moon

It is an invention that was the seed of a multinational company that today markets thousands of products.

Have you guess it? Here’s another clue.

The word popularly used to designate this product actually corresponds to a trademark, not to the object itself. It is a case of metonymy.

Do you know what invention we’re talking about? Not yet? Then, carefully read the history of this invention.

It all began in 1941 in the Swiss Alps. George de Mestral, a thirty-something Swiss electronics engineer, was back from a walk in the mountain with his dog, removing the burrs that had stuck to the dog’s hair and his clothing during the walk. These small spiked balls are the fruits of some plant families, and their ability to attach to animal hair is an advantage of these species as it helps to disperse the seeds that are inside the fruit.

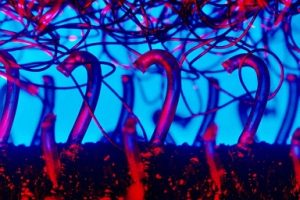

The story goes that at that moment Mestral wondered why the burrs stuck and decided to look at them with a microscope in his house. The engineer then noticed that the fixation occurred between two elements. On the one hand, tiny loops formed on the matted coat of the dog or on the surface of the tissues. On the other hand, the tips of the little thorns, which were shaped as a hook. These flexible little “hooks” were tangled in the loops and only loosened by pulling them out with some force. With a biomimetic look and inventive spirit (Mestral presented his first patent at age 12), he saw in this natural system of reversible fixation, a model to artificially develop a very useful product.

Have you guessed what the invention is? Whether yes or no, see how the rest of the story.

For some years, George de Mestral faced the challenge of creating a prototype of this system of tiny hooks and loops. The main problem was to develop a method which would allow manufacturing a strip of fabric that could push upward, perpendicularly, a considerable amount of flexible hooks.

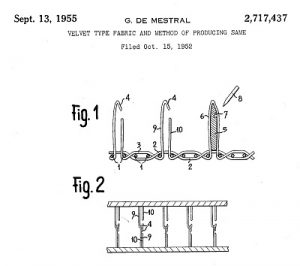

It seems the process was not easy, and that Mestral had a hard time finding people to help him produce this fabric. However, in 1952, he filed a patent application with the United States patent office about such a fabric and how to fabricate it. In the document, Mestral presented a “velvet-like fabric,” as it was covered, like velvet, with a dense “forest” of upright wires. However, unlike velvet, in the new fabric the threads were made of nylon (a newly created material), and a good part of the threads had hook-like tips. The manufacturing process proposed in the patent was similar to traditional velvet, using a loom, but with a few additional tricks to shape the hooks at the ends of the nylon strands.

Granted in 1955, this seems to be the first in a series of patents by the Swiss engineer around the invention that is the answer of our guessing game.

Mestral then founded a company to manufacture and market the product. However, the manufacturing system he had proposed in the patent was not fully mechanized and did not allow it to be produced at an industrial scale. The finishing process to produce the hooks was manual… and quite time consuming. The engineer had to wait about 20 years from his “eureka!” for a loom capable of mass producing the fabric with the tiny hooks.

When coupling the fabric with the hooks with another fabric covered by a tangle of loops, Mestral obtained a reversible fixation product with a thousand and one utilities, and with potential to revolutionize the market of zippers and buttons.

At first, the system invented by Mestral did not look very attractive. But little by little he gained visibility (from newspaper columns to futuristic films) and was adopted by various segments. In the late 1960s, for example, the invention began to be used by sports shoes manufacturers, replacing shoelaces and stood out in the NASA space program “Apollo” as a system to attach small objects to the walls of the spacecraft, preventing them from floating.

Currently the product is incredibly widespread. It helps solve small day-to-day problems in offices, shops, residences, hospitals, laboratories, walkways, schools…

Need another clue to guess what the invention is? Here goes the last one:

In 1956, George de Mestral obtained the trademark registration for his company. The name invented by the Swiss is the combination of two words in French (predominant language in the region of Switzerland where he was born and died): “velours” (velvet) and “crochet” (hook).

We do not need to pronounce the name of this invention, do we? Mainly because it’s forbidden to use the term “Velcro ®,” as it is a registered trademark of this multinational company which markets this and other similar products, and is also the trademark used for all the company products, not just for “hook and loop fastener.” Go explain this to the children, who really like V________, especially in sports footwear…